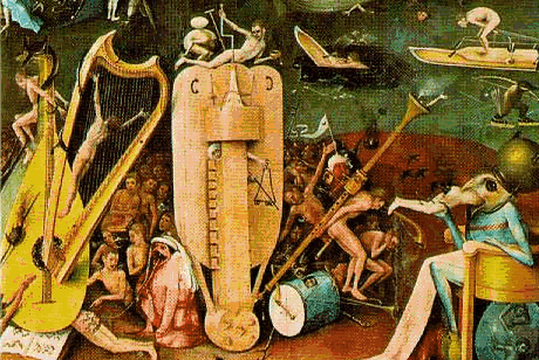

Artwork by author/artist and friend, Sandra Schwab, who I also owe special thanks for her research assistance on this post! Visit her at www.sandraschwab.com. Artwork by author/artist and friend, Sandra Schwab, who I also owe special thanks for her research assistance on this post! Visit her at www.sandraschwab.com. As today, music was a popular form of entertainment in the Middle Ages — for who doesn't like dancing or singing? In Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, several of the pilgrims in the frame story have musical talents. Among them is Madam Eglantyne, the Prioress, who makes sure to sing prettily "with a fine / Intonation through her nose, as was most seemly." Similarly, the Friar's voice is described as merry: He sings well, plays a small harp — and when it comes to singing ballads (not quite what a friar was supposed to do), he always takes the prize. The brash and loud Miller, whose temper is as fiery as his beard, plays an equally loud instrument, the bagpipes, and in the tale he tells, "hende Nicholas" (the guy is very good with his… eh… hands) (yes, that way too) plays the psaltery.  But for the upper classes, too, musical talents were important. Not surprisingly then, Chaucer's handsome young squire, the embodiment of the ideal courtly lover, is multi-talented: "He knew the way to sit a horse and ride. / He could make songs and poems and recite, / Knew how to joust and dance, to draw and write." Indeed, we know that even King Richard the Lionheart wrote songs and had a good singing voice. Yet, this is hardly surprising, given the French roots of his family: It was his French mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, who brought a lot of elements of the refined southern French culture to England, and it was in what is now southern France that a high-medieval tradition of song-writing in the vernacular first emerged at some point in the late 11th century. We don't know exactly when, because medieval music was mainly an oral tradition, and much of it was lost. :( The first of this new kind of poet-composers, called troubadours, we know by name is Guilhelm, Duke of Aquitaine (1071-1126). Many of the troubadours came from aristocratic families, and if they didn't, they typically had a noble patron. The art of the troubadours thus came to be firmly connected with aristocratic courts and aristocratic language, and one of the main topics of their works was courtly love. LIKE THIS gorgeous performance by Annwn of an authentic courtly love song from the 1300s. (Take a good look at the aching beauty of those lyrics compared to the crude way women are addressed in lyrics today.) But, moving away from the lofty sentiments of chivalry, there were other, less refined kinds of musical entertainers, too — most of whom incited the wrath of the Church with their "ungodly" behavior and licentious songs. At the end of the 13th century, Thomas de Cobham, the Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote about three kinds of professional entertainers and the probably fate that awaited them after death:

The archbishop subdivided this third group into those who play songs at public houses and incite others to licentious behavior (=> all going to hell) and those whose who sing about the noble deeds of princes and saints and thus bring comfort to the people => Heavenly salvation possible, hooray. IF they didn't muck it up in some other way. The archbishop uses the Latin histrio as an umbrella term for all three kinds of professional entertainers. The term that we today most likely associate with medieval musicians is minstrel, from Latin ministerialis, "office-holder". By the 12th and 13th centuries, the term was used for musicians and included those who sang and accompanied themselves on an instrument such as a small harp. By the 14h century, however, the meaning of the term had narrowed and minstrel seems to have been used mainly for instrumentalists — and by the 15th century mainly for players of wind instruments (e.g. trumpet, flute, shawm, and bagpipes), though the meaning could be expanded by adding a qualifier as in "string minstrels." Apart from the harp, there were various other string instruments in the Middle Ages, ranging from the fiddle to the curious-looking hurdy-gurdy. New instruments reached Europe through contacts with the Islamic world, among them the citole and the lute. In addition to the wind and string instruments, minstrels also used percussion instruments, that is different forms of drums as well as bells. Initially, the majority of musicians would have traveled from place to place and we find them playing at jousts and tournaments, at fairs and local festivals, and at weddings in the slowly growing towns. Many would have traveled in groups, which not only offered greater protection from robbers on the road, but also meant their entertainments could be more varied and eye-catching. Thus, on the market places across Europe, you could find acrobats performing marvelous feats to music as well as musical acts that included performing dogs or even dancing bears (or well, nude dancing). But musicians were also employed by kings and the aristocracy to perform at court and during feasts. When travelling, nobles often took along musicians who played loud instruments such as trumpets, shawms or bagpipes to announce their presence. Especially at royal and noble courts, musicians could earn large sums of money, whereas the life of itinerant minstrels must have been very hard at times — and it wasn't just a matter of money. Minstrels didn't have the same rights as ordinary citizens and no legal protection. In order to overcome the prejudices against them and to gain more rights for themselves, minstrels living in cities started to form guilds. This way they were also able to protect their own interests, for example by securing performance rights for members of the guild and making sure that wandering musicians wouldn't be offered employment. Musicians employed at courts often followed a similar strategy. As a result, the life of a wandering minstrel became less and less attractive and less and less lucrative. As a result their numbers sharply declined during the 15th century. By this time, they were thought to be no better than beggars and vagabonds. SCROLL DOWN FOR ANOTHER VIDEO ~ To see how these medieval rockers could really get jammin'! To find out more: A list of medieval wind instruments: http://www.medievalminstrels.com/instruments_wind.php A list of medieval string instruments: http://www.medievalminstrels.com/instruments_string.php A list of medieval percussion instruments: http://www.medievalminstrels.com/instruments_percussion.php The hurdy-gurdy explained: https://youtu.be/r4y7HNW972M A 13th century English dance tune, performed on the harp: https://youtu.be/4Bf1bFOf4Gg Various interpretations of the most famous medieval song in English, the rota (or round) "Sumer is icumen in" (below! Trans: Summer Has Come): Vocal 1: https://youtu.be/EHFxxZmyxDg Vocal 2: https://youtu.be/AB-ct-cDX3w Instrumental: https://youtu.be/kWVRvz3xIfg Rockin' like it's 1252!Quotes and images for this article:

Chaucer quotes: from Geoffrey Chaucer. The Canterbury Tales. Transl. by Nevill Coghill. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2003. Picture of Chaucer's Miller: illustration from the Ellesmere Chaucer, an early 15th-century manuscript of The Canterbury Tales, held at the Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, CA. Wikipedia Commons. Picture of the hurdy-gurdy player: By Sander van der Wel - Flickr: Elf Fantasy Fair 2010, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14750532

0 Comments

|

FOLLOW ME ON:

My Latest Release!

Duke of Shadows

A heartbroken belle, a missing suitor, and a heroic duke in disguise. Archives

April 2020

|

Privacy Policy

Cookies Policy

Terms of Service

RSS Feed

RSS Feed